Atmospherics

This file will be written in the first person in the interest of having a laid back style, as some of the concepts here would be ass to read as technical writing. Understand that this isn't the work of one person, but the combined efforts of several contributors. It is a living document, and one you should strive to keep up to date. I have Now, the purpose of this bit of documentation. Over the history of /tg/ there have been several periods where one or no active coders understood how atmospherics works, or even how it was intended to work. We've lost several major pieces of functionality, not because none knew how they worked, but because none knew that they should work, or even that they existed. Atmospherics tends to be a somewhat cloudy corner of our codebase, unless you know exactly what to look for noticing that something is broken can be a feat in and of itself. My goal here is to solve that problem once and for all. Not everything will be documented in this file, I won't go line by line. I will however describe how things ought to work, and how some of the more complex stuff is meant to run. Atmospherics is a very complicated and intimidating system of SS13, and as such very few contributors have ever made changes to it. Even fewer is the number of contributors who have made changes to the more fundamental aspects of atmos, such as Environmental Atmos or gas mixtures. There are several other factors for this, of course. In the case of Environmental, its arcane nature coupled with its extremely important gameplay effects leave it a very undesirable target for even the least sane coder. As for gas mixtures, they were virtually untouchable without extensive reworks of the code. This paste-bin is a good example; it lists all the files one would need to make changes in order to add a new type of gas in the old system. As you can imagine, the sheer bulk of work one would need to do to accomplish this essentially invalidated any such attempts. However, my primary goal is to bring atmos to a state where any coder will be able to understand how and why it works, as well as cleanly and relatively easily make changes or additions to the system. While much progress to this end has been achieved, still very few have taken advantage of the new frameworks to try to implement meaningful features or changes. The purpose of this document is to lay out the inner workings of the entire atmos system, such that someone who does not have an intimate understand of the system like myself will be able to contribute to the system nonetheless. Recognizing this desire, I hope and believe that you who are reading this are willing to learn and contribute. Thank you. Hello! So glad you could join us. Atmospherics is the system we use to simulate gases. Might as well get that out of the way. It is made up of several major parts, and a few more minor ones. We'll be covering the air subsystem, gas mixtures, reactions, environmental flow, and pipenets in the document. If you'd like to understand more about how environmental atmos works after reading the relevant subsection, go to Appendix B. It discusses how to properly visualize the system, and what different behavior looks like. Now then, into the breach.

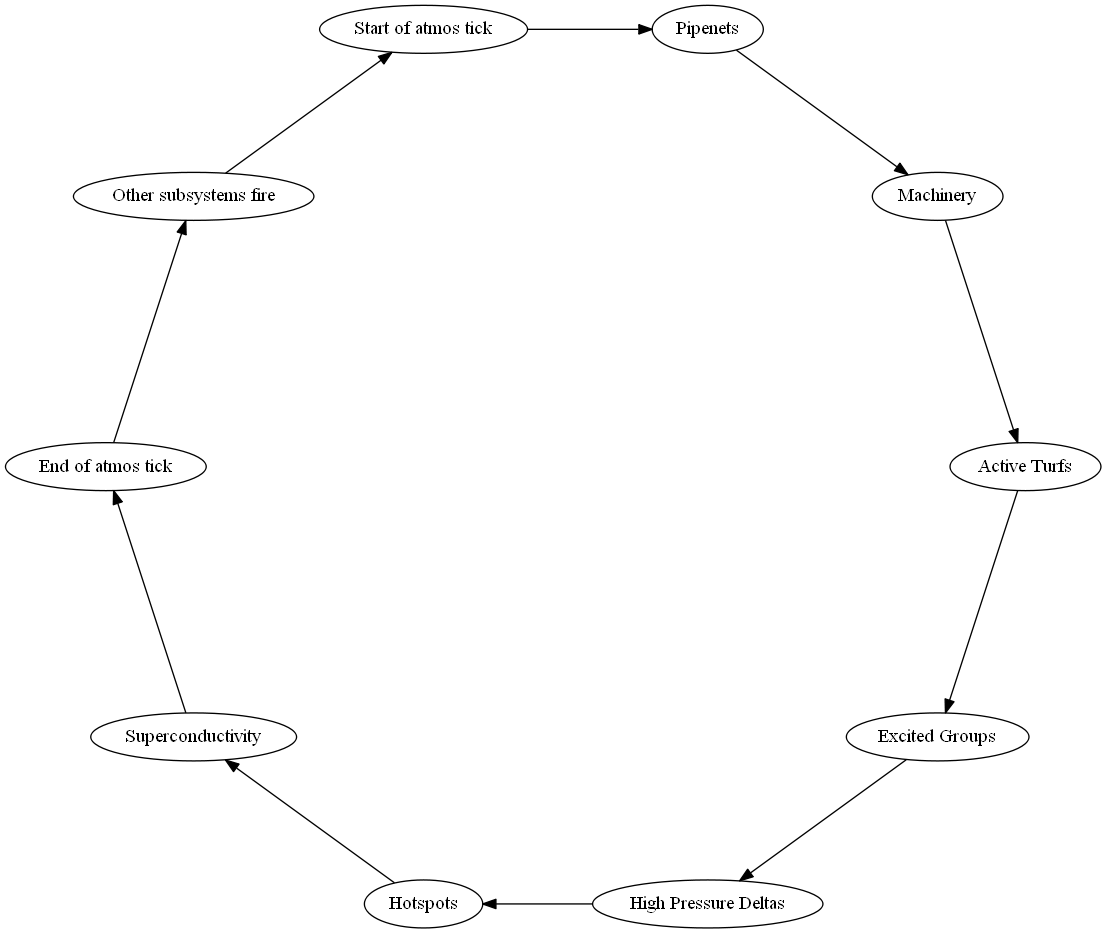

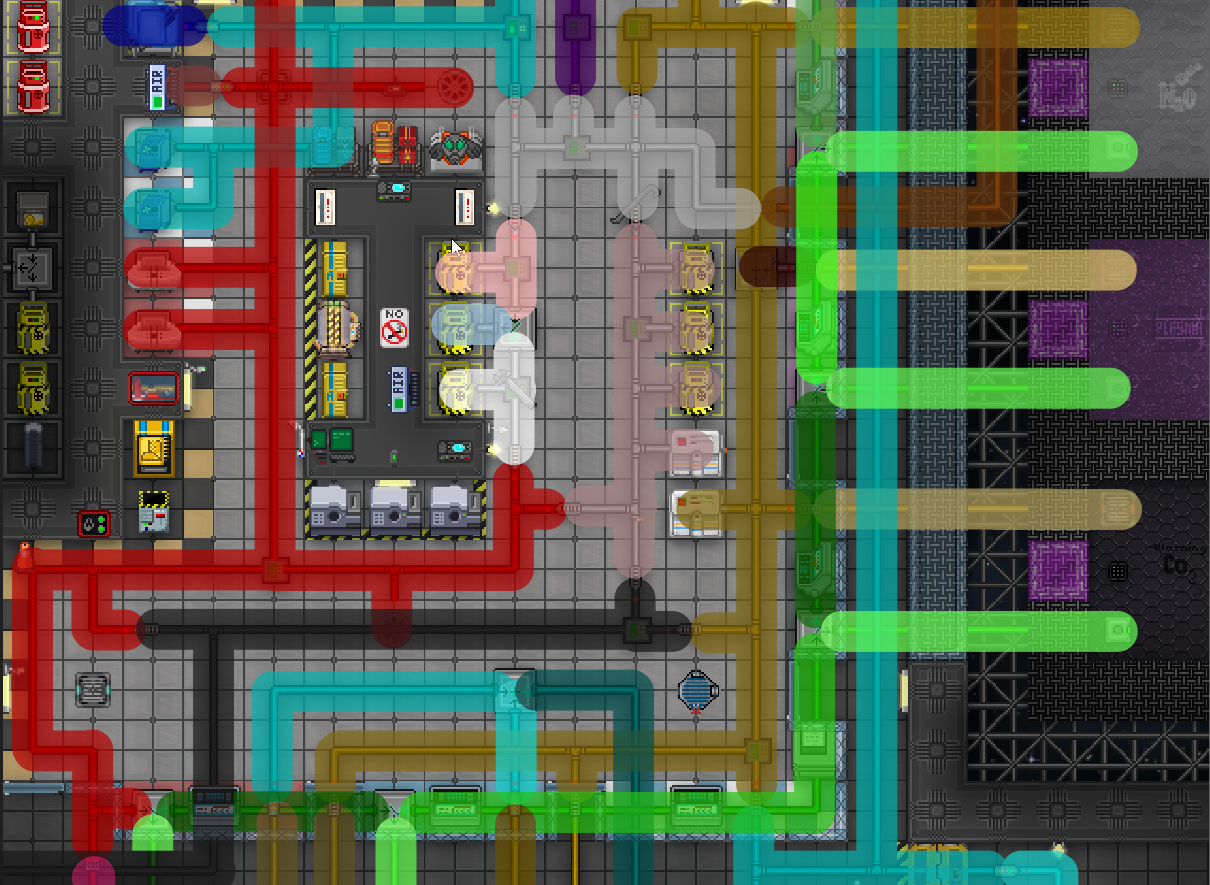

Figure 3.1: The structure of one air controller tick. Not totally accurate, but it will do The air controller is, at its core, quite simple, yet it is absolutely fundamental to the atmospheric system. The air controller is the clock which triggers all continuous actions within the atmos system, such as vents distributing air or gas moving between tiles. The actions taken by the air controller are quite simple, and will be enumerated here. Much of the substance of the air ticker is due to the game's master controller, whose intricacies I will not delve into for this document. I will however go into more detail about how SSAir in particular works in Chapter 6. In any case, this is a simplified list of the air controller's actions in a single tick:

If the air controller is the heart of atmos, then gas mixtures make up its blood. The bulk of all atmos calculations are performed within a given gas mixture datum (an instance of Gas mixtures contain some of the oldest code still in our codebase, and it is remarkable that overall, the logic behind the majority of gas mixture procs has gone unchanged since the days of Exadv1. Despite being in some sense "oldcode", the logic itself is quite robust and based in real world physics. Thankfully, gas mixtures already are quite well documented in terms of their behavior. Their file is well commented and kept up to date. I will, however, elaborate on some of the less obvious operations here. Additionally, I will document the structure of gas lists, and how one should interface with a gas mixture should you choose to use one in other code. Now don't be scared by the code mind, it's SPOOKY PHYSICS but it's not the devil, we can break it down into component parts to understand it. Snippet 4.1: excerpt from The snippet above is an example of one particularly strange looking calculation. This part of share() is updating the temperature of a gas mixture to account for lost or gained thermal energy as gas moves to/from the mixture, since gases themselves carry heat. To understand this snippet, it is important to understand the difference between heat and temperature. For the most part, the average coder need only concern himself with temperature, as it is a familiar experience for anybody. However, internally in atmos, heat (thermal energy) is the truly important quantity. Heat is defined as temperature multiplied by heat capacity, and is measured in joules. Typically within atmos, we are more concerned with manipulating heat than temperature; however, temperature is tracked rather than heat largely to make interfacing with the system simpler for the average coder. Thus, this snippet modifies heat in terms of temperature - it adds/subtracts three terms, each of which measure heat, to determine the new heat in the gas mixture. This heat is then divided by the mixture's heat capacity in order to determine temperature. One trick to understanding passages like this is to do some simple dimensional analysis. Look only at the units, and ensure that whenever a variable is assigned that it is being assigned the appropriate unit. The snippet previously discussed can be represented with the following units: The true beauty of the gas mixture datum is how it represents the gases it contains. A bit of history: gas mixtures used to represent gas in two ways - there were the four primary gases (oxygen, nitrogen, carbon dioxide, and plasma) which were hardcoded. Each gas mixture had two vars (moles and archived moles, a concept to be explained later) to represent each of these gases. Calculations such as thermal energy made use of predefined constants for these hardcoded gases. The benefit of this was that they were extremely quick - only a single datum var access was needed for each one. In contrast, there were trace gases, for which there were a list of gas datums. The only trace gas available in normal gameplay was nitrous oxide (N2O or sleeping agent), though through adminnery it was possible to create oxygen agent B and volatile fuel, curious gases which will be described later for historical reasons. Trace gases, in contrast to hardcoded gases, were quite modular. To add a new trace gas one needed only to define a new subtype of /datum/gas and add appropriate behavior wherever desired, such as breath code. Unfortunately, of course, trace gases were slooooow. Calculations on trace gases were significantly more costly than hardcoded gases. The problem was obvious - it seemed impossible to have a gas definition which shared the modularity of trace gases without sacrificing too much of the performance of the hardcoded gases. What then to do? There was no option to port an improvement from another codebase. As far as I am aware, there have been no significant downstream improvements to gas mixtures. The other major upstream codebase, Baystation12, uses a very different atmos system; in particular, their XGM gas mixtures have their own solution to this problem. To summarize XGM, there is a singleton which has associative lists of gas metadata (information such as specific heat, or which overlay to display when the gas is present) which gets accessed whenever such information is needed. To count moles, each gas mixture has an associative list of gas ids mapped to mole counts. There were a couple of problems with this approach: 1. There was no measure of archived moles. While it would be easy to simply add a second associative list, this has non-trivial memory implications as well as a potential increase to total datum var accesses within internal atmos calculations. 2. The singleton used for storing metadata helps with the memory impact that using full datums would have, but does not properly address the cost of datum var accesses, as to access metadata you must still access a datum var on the singleton. For some time, without a clear solution, we simply stuck to the status quo and left gases non-modular. Eventually, however, there was an idea. Enter Listmos. The solution we came to was beautifully simple, but founded on some unintuitive principles. While datum var accesses are quite slow, proc var accesses are acceptable. If we use a reference for a given var, this can be exploited by "caching" the reference inside of a proc var. How can we take advantage of this without using a datum, thus nullifying the benefit? The answer was to use a list. The critical realization was that a gas datum functioned more so as a struct than as a class. There were no procs attached to gas datums; only vars. While DM lacks a true struct with quick lookup times, a list works very well to perform the same function. Thus, the current structure of gas was created, under the name Listmos. Each gas mixture has an associative list, gases, which maps according to a key to a particular gas. This gas is itself a list (not an associative list, mind) with three elements; these elements correspond to the moles, archived moles, and to another list. This final list is a singleton - only one instance of it exists per gas, and all gas instances of a particular type point to this same list as their third element. The final list contains the metadata for the gas, such as specific heat or the name of the gas. The structure of the metadata list varies according to how many attributes are defined overall for all gases, but it is also non-associative since the structure can never change post-compile, so we save a little bit of performance by avoiding associative lookups. Each type of gas is defined by defining a new subtype of /datum/gas. These datums do not get instantiated; they merely serve as a convenient and familiar means for a coder unfamiliar with the inner workings of listmos to define a new gas. Additionally, the type paths serve a second use as the keys used to access a particular gas within the gases list. It is easiest to demonstrate the manipulation of gas, including these list accesses, with an example. Snippet 4.2: gas mixture usage examples Of particular note in this snippet are the two procs assert_gas() and garbage_collect(). These procs are very important while interfacing with gas mixtures. If you are uncertain about whether a given mixture has a particular gas, you must use assert_gas() before any reads or writes from the gas. If you fail to use assert_gas() then there will be runtime errors when you try to access the inner lists. When you remove any number of moles from a given gas, be sure to call garbage_collect(). This proc removes all gases which have mole counts less than or equal to 0. This is a memory and performance enhancement for list accesses achieved by reducing the size of the list, and also saves us from having to do sanity checks for negative moles whenever gas is removed. As a quick reference, here is a list of common procs/vars/list indices which the average coder may wish to use when interfacing with a gas mixture.

While we're on the subject, The second is

While defining a new gas on its own is very simple, there is no gas-specific behavior defined within /datum/gas. This behavior gets defined in a few places, notably breath code (to be discussed later) and in reactions. The most important and well known reaction in SS13 is fire - the combustion of plasma. Reactions are used for several things - in particular, it is conventional (though by no means enforced) that to form a gas, a reaction must occur. Creating a new reaction is fairly simple, this is the area of atmos that has received the most attention over the last few years, and the best place to start. Don't be scared of the size of reactions.dm, it's not that complex. There are two procs needed when defining a new reaction, /datum/gas_reaction/proc/init_reqs() and /datum/gas_reaction/proc/react(). init_reqs() initializes the requirements for the reaction to occur. There is a list, min_requirements, which maps gas paths to required amount of moles. It also maps three specific strings ("TEMP", "MAX_TEMP" and "ENER") to temperature in kelvins and thermal energy in joules. More behavior could easily be added here, but it hasn't yet for performance reasons because no reactions have need of it. As for react(), it is where all the behavior of the reaction is defined. The proc must return one of NO_REACTION, REACTING, or STOP_REACTIONS. The proc takes one or optionally two arguments. The first, mandatory, argument is a gas mixture on which to perform calculations; this mixture is what is reacting. The second, optional, argument is a turf or pipenet, specifically the thing which contains the gas mixture. You may choose for the reaction to affect the object in some way. Note that it is conventional for constants within reactions to be #define'd at the top of the file and #undef'd at the end. This is a rather large subject, we will need to cover gas flow, turf sleeping, superconduction, and much more. Strap in and enjoy the ride! Share()Each pair of turfs will only ever call That means turf A calling share on turf B should work the same as turf B calling share on turf A The key idea of FEA, the core sharing system we use is that neighboring cells should effectively equalize with each other. So taken on a line, you'd have two sharing partners, the cells to your left and right. The end goal of the simulation is for all the tiles on the line to have the same mix. But we can't just jump to that. So each "tick" we take our mix and average it with the mixes of the two tiles next to us. There's an equation for this that's considered standard in heat simulation. (Watch this video: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ly4S0oi3Yz8) We can't use it because means each pair of turfs needs to talk to each other twice, which is pain expensive. That and I'm pretty sure it would prevent us from yielding So instead of a complex form of averaging, we portion up tiles. So if you have two neighbors and you have something they don't, you can give them each a third. Have to keep one for ourselves mind, because otherwise we'll run out of gas. They can then act on this portion however they like, and we can likewise act on a portion of them to our liking. We know how much gas a tile had at the outset because of the archived moles list index. If we take more then we're owed in any shares before all other turfs have had their say, we could end up with negative moles. We expend a lot of effort to avoid this. The math for this looks like (totaldeltagas)/(neighborcount + 1) You may notice something like this in Back in the old FEA days, neighbor count was hardcoded to 4 (Likely because this is what cell sharing on an infinite grid would look like). This means that turf A -> turf B is the same as turf B -> turf A, because they're each portioning up the gas in the same way. But when we moved to LINDA, we started using the length of our atmos_adjacent_turfs list (or an analog). We need this so things like multiz can work, and so tiles in a corner share in a way that makes sense. Because of this, turf A -> turf B was no longer the same as turf B -> turf A, assuming one of those turfs had a different neighbor count, from I DON'T KNOW WALLS? The fix for this was to use our neighbor count when moving gas from our tile to someone else's, and use the sharer's neighbor count when taking from it. This makes sense intuitively if you think of it like portioning up a tile, but I've included a rundown to make it a bit easier to prove to yourself. Take a lookI have 10 You have 20 let's share I've got 2 partners you've got 3 partners so you want to give me 1/4th of your gas I want to give you 1/3rd of my gas the total gas diff between me and you is -10 since it's negative you get to decide how to portion it so the total amount to share is -2.5 I end up with 12.5 you end up with 17.5 again total diff is -5 to share is 1.25 I end up with 13.75 you end up with 16.25 again total diff is -2.5 to share is 0.3125 I end up with 14.0625 you end up with 15.9375 We need to do this because if the portions get mixed up, our archived gas list ends up lying about how much of each gas type we have available to share. This can lead to negative moles, which the system is not prepared for. This is also why we queue space's sucking till the end of a tile's

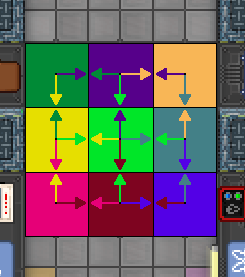

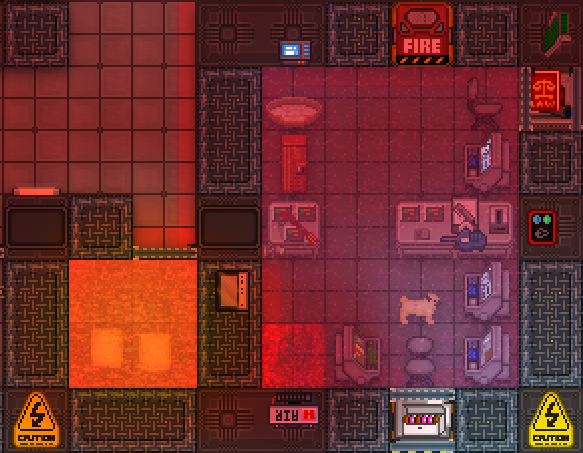

Figure 5.1: A visual of the algorithm Active turfs are the backbone of how gas moves from tile to tile. While most of

Alright then, with that out of the way, what is an active turf. This is actually the main success of LINDA, the math for gas movement is r4407 goon code or older, but that implementation (FEA) had a glaring issue. All turfs processed, or rather, all The major difference between then and now is our turfs will stop processing. They sit idle most of the round, wake up when something changes around them, process until no major changes are happening, and then go to sleep. Active turfs also poke all the listening objects sitting on them, and start to process them so they can react to heat or gas changes. We do this so objects don't need to process when nothing has changed, but they also can operate through a turf sleeping. In essence this is like waking up things that ought to be listening to us. If we just used active turfs sleeping would be easy as pie, we could do it turf by turf. But we don't.

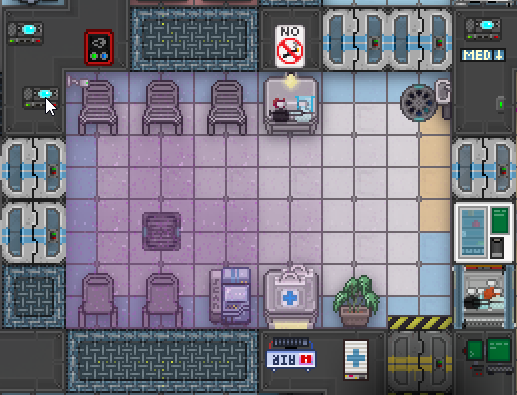

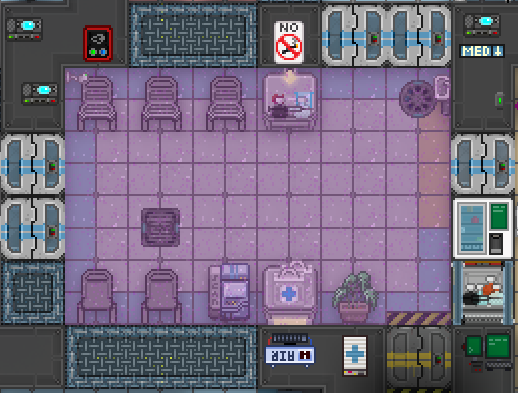

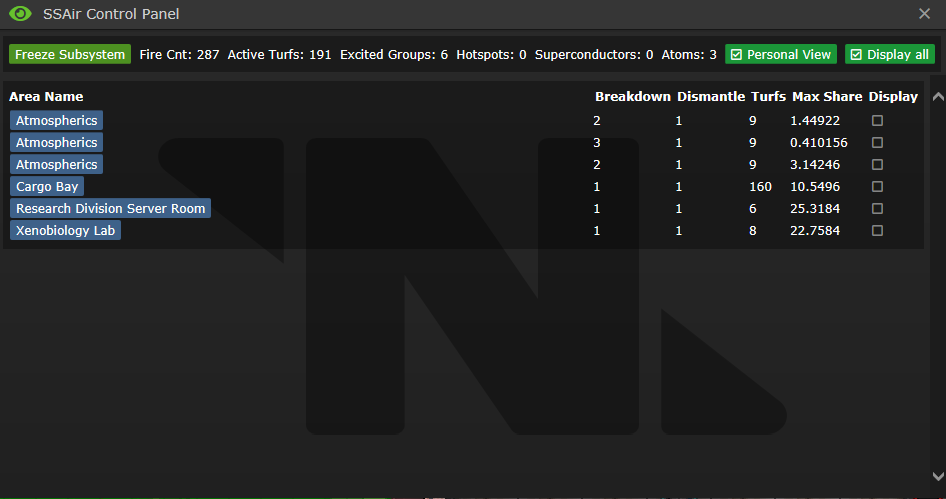

Figure 5.2.1-5.2.2: Settled VS Unsettled gases, this is what excited groups do I didn't mention this above, but active turf processing, or really With only active turfs breaches would never settle, and as soon as a tile becomes active it would never rest again. (This is one of the reasons I wrote this document by the way, excited groups nearly totally broke around about 2016, and none at the time noticed because the code was so twisted none knew how it ought to work, so it persisted for 4 years past that) So active turfs are bad at evening out diffs. What can we do to solve this? Enter the excited group. We hold a list of all the turfs that have talked to each other, then we keep track of how active those turfs are. When they start to wind down, we spread all the gas out evenly between them, and the group starts to spread again. They tend to fill the space given to them, so be careful with open plan stations. This is I've been talking kinda abstractly about turfs sleeping. That's because turfs on their own don't stop waiting to process once they have an excited group. Groups have secondary roles as the grim reaper of active turfs. When a group is totally inactive, and nothing whatsoever is going on, it will Excited groups can tell the amount of diff being shared by hooking into a value Now this would all be fine, but as I'm sure you've noticed, there's a crouching pile of lag hiding here. What happens if the excited group has turfs with a fire on them over in cargo, but the flow of gas started in medical? There's no point processing the majority of the tiles, but we still want to keep the group alive for equalization. Originally LINDA only had the above 2 constructions, but we ran into a problem when making planetary turfs. The old implementation was mutable, but shared with a copy of its initial mix each tick. This lead to problems. In essence, the groups never stopped spreading so long as a source of diffs existed. This is because the job of excited groups is to move the diffs from the source, to the edges of the group. But we put these mixes on huge open planets. Doesn't really work out so well. To combat this, a timer was added to each turf. It reset when a significant share was made, but otherwise if enough time passed the turf was forcibly removed from the active_turfs list. Unfortunately for us, this had unintended side effects. When a turf is removed from active, the excited group is broken down, as it's assumed that the proc will only be called when the landscape of the map itself has changed. You begin to see the issue. With large enough space, excited groups broke, totally. Constant rebuilds into dismantles, cycling forever. Now this issue here is we'd like to keep this napping, but we don't want to So, a new proc was added, You'd think this would cause issues with maintaining the shape of an excited group, however this isn't actually a priority, since There's another issue here however, how do we deal with things that react to heat? A firelock shouldn't just open because the turf that the alarm is on went to sleep. Thus, atom_process, as I mentioned before, a list of atoms with requirements and things to do. It processes them until their requirements are not met, then it removes them from its list them. There's one more major aspect of environmental atmos to cover, and while it's not the most misunderstood, it is the code with the worst set dressing.

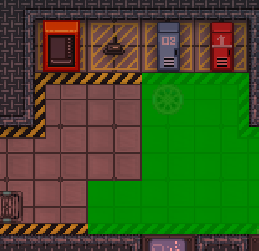

Figure 5.3: The death of a pug, and a visual description of what superconduction does Superconduction, an odd name really, it doesn't really describe much of anything aside from something to do with heat. It gets worse, trust me. Superconduction is the system that makes heat move through solid objects, so in theory walls, windows, airlocks, so on. This is another one that just broke one day, and none noticed cause none knew what it was meant to do. There's another issue with it, the var names don't mean what you think, and it is very old code, so it's hard to grasp. You can do it, you've made it this far. So then, what does superconduction do, and what do all these damn vars mean. As I mentioned above, superconduction shares heat where heat can't normally travel. It does this by heating up the turf the heat is in, not the gasmix, the turf itself. This temperature is then shared with adjacent turfs, based on There's one more, and it's a doozy. So then, a review.

One more thing, turfs will superconduct until they either run out of energy, or temperature. This is a stable system because turfs "conduct" with space, which is why floods of heat will equalize to about 690k over time. This will require/impart a light understanding of the master controller, I will go over what makes the atmos subsystem slow, what can be done, and what it effects. First, some new vocab.

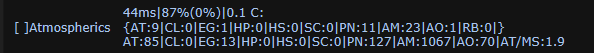

The MC entry for SSAir is very helpful for debugging, and it is good to understand before I talk about cost.

Figure 6.1: SSAir sitting doing little to nothing turf wise, only processing pipenets and atmos machines If you aren't familiar with the default subsystem stats, you can see them explained here: [][http://codedocs.tgstation13.org/.github/guides/MC_tab.md] The second line is the cost each subprocess contributed per full cycle, this is a rolling average. It'll give you a good feel for what is misbehaving. (The only exception to this is pipenet rebuilds, the last entry. Because of its nature as something that can happen at any time, it doesn't have a rolling average, instead it just displays the time it used last process) The third line is the amount of "whatever" in each subprocess. Handy for noticing dupe bugs and crying at active turf cost. Speaking of, the last entry is the active turfs per overall cost. Not a great metric, but larger is better. Now then, what the hell is going on in that image. SSAir has a wait of 5 deciseconds, or 500ms. This means it wants to fire roughly twice a second. You'll see in a moment why this hardly ever happens. See that image from before? Notice how the cost of SSAir at rest is about 40ms? yeahhhhh. The atmos subsystem was used as a testing ground for the robustness of the master-controller. It used to have a wait of 2 seconds, but that was lowered to 0.5 as it was thought that the system could handle it. It can! But this can have annoying side effects. As you know, we edge right up against 1/10th of the wait when sitting at rest, and if we start to make diffs...

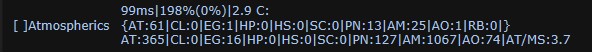

Figure 6.2: SSAir when a high amount of active turfs are operating, with a large selection of gastypes for each tile As you can see, active turfs can be really slow. Oh but it gets so much worse. Active turf cost is mostly held up in For this reason, and because excited groups spread gas out so much, we want to keep the variation of gastypes in the air relatively low. react() is called for every active turf, and every pipenet. On each react call for reasons I don't want to go into right now, we need to iterate over every reaction and do a preliminary test. Therefor, the more datum reactions we have, the slower those two processes go.

Figure 6.3: The effects of a large excited group on overtime It's hard to tell here because I took the picture right as it happen, but when large excited groups go through On the whole excited groups are the only major source of overrun, consider this a treatise on why that 900ms cost number next to atmos isn't making the server die. It's really that excited group mass equalizing constantly.

Figure 7.1: Diffs settling out as they should, around their sources Our goal is not to simulate real life atmospherics. It is instead to put on a show of doing so. To sleep wherever we can, and fake it as hard as possible. This is matters the most with environmental stuff, but it's everywhere you look. The goal of active turfs, excited groups, and sleeping is to isolate the processing that needs to happen, and move diffs from their source to a consumer as much as we can. We don't simulate every tile, and most of the changes to LINDA have been directed at simulating as little as we can get away with. Hell, space being cold is a hack we use to make gameplay interesting. There's a lot more stuff like this, because this isn't a simulator, it's a theater production. Performance and gameplay are much more important then realism. In all your work on the subsystem, keep this in mind, and you'll build fast and quality code.

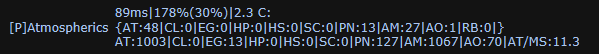

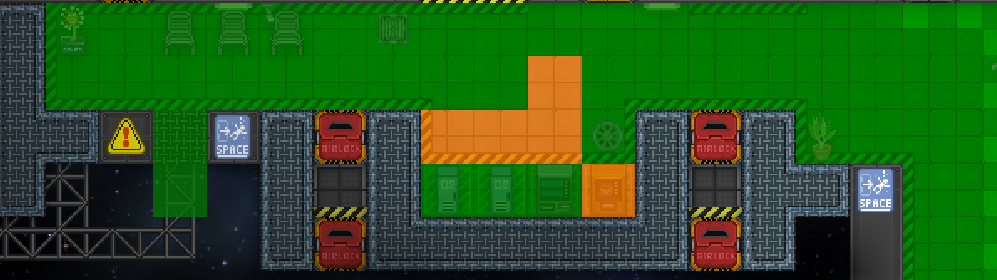

Figure 8.1: The structure of pipelines shown in color, components are a mix

To understand pipelines you'll first need to understand how we process things like pumps or vents, atmos components that is. To start with, a set of pipes is treated as one gas mixture, however several different components draw from this mix. Think pumps, heaters, mixers, vents, etc. Since these components change the mix itself, we can't just let them all act on the mix at once, because that would cause concerns around the order in which things process, and so on. We don't want canisters that blow up half the time, and the other half of the time don't. Better then to give each component its own gas mix that it alone can act on, that will be shared with the pipeline as a whole. Pipelines do something similar to active turfs by the way, they won't re-equalize their mix if nothing about the state of things has changed. We do this sharing based on the proportion of volume between all the components. So if you want a component to consume more gas, give it a higher volume. On that note, I'd like to be clear about something. In lines of connected pipes, each pipe doesn't have its own gasmix, they instead share mixes, as the pipes themselves won't have any effect on the state of the mix. Oh, and pipelines react the gas mixture inside them, thought I should mention that. Everything that needs a pipeline should have it before it's allowed to do any processing. This is to prevent runtimes and shitcode related things. The act of rebuilding a pipeline is quite expensive however, since it involves iterating over all the connected pipes/components. That's why we go to such great pains to make sure no large amount of work is allowed to happen at once. It's in an attempt to avoid the excited group settling type of lag I discussed above. It's ok for atmos to lock up for a short period if the system isn't killing the game as a whole. All the other behavior of pipes and pipe components are handled by atmos machinery. I'll give a brief rundown of how they're classified, but the details of each machine are left as an exercise to the reader. The raw pipes. They have some amount of nuance, mostly around layers, but it's not too tricky to deal with. The HE pipes, used to transfer heat from the pipe to the turf it's sitting on. These work directly with the pipeline's mix, which is ehhhh? Might need some touching up, perhaps making them subnets that do one heat transfer. Not too big a deal in any case, since they're the only thing that acts directly on a pipeline mix. They have some other behavior, like glowing when hot, but it's minor. These are the components I described above, they have some sort of internal gas mix that they act on in some manner. The following classifications are very simple, but I'll run them over anyhow Unary devices can only interact with one pipeline, aside from some exceptions, like the heat exchanger. The type path comes from the amount of pipelines a device expects gas-mixtures from. I'm sure you can see where this is going. Binary devices connect to 2 pipelines. Trinary devices connect to 3 p- Listen you get it already. Finally something more interesting. Unfortunately I'm not familiar with the inner workings of this machine, but this folder deals with hypertorus code. This is for the oddballs, the one offs, the half useless things. Things that are tied to the module, but that we don't have a better spot for. Think meters, stuff like that. These are the atmos machines you can move around. They interface with connectors to talk to pipelines, and can contain tanks. Not a whole lot more to discuss here. You may have noticed that a large portion of the optimizations we do are focused around not checking to see if we need to do work. This is essentially what active turfs are built around, and it's a somewhat unfinished project. There's still quite a few things in atmos, mostly machinery, that check each fire to see if they should be doing work. There's a general pattern to solving this sort of thing by the way, centralize the ways a bit of outside code can interact with a "thing", and then when the outside code does something that might warrant processing, start processing. This attitude needs to be applied to a few large targets, and you may see it crop up when reading through the code. Keep this in mind, and make sure to respect the rules that describe how to work with the object, or things will go to shit.

If you really want to get a feeling for how flow works you'll need to load up the game and make some diffs. What follows is a short description of how to set up testing. To start with, you should enable the Past that you'll want to turn on excited group highlighting, to do this open the atmos control panel in the debug tab and toggle both personal view and display all. Display all makes turfs display their group and personal view shows/hides the groups from you, it's faster to toggle this, and this way you don't piss off the other debuggers on live.

Figure B.1: The atmospherics control panel To go into more detail about the control panel, it is split into two parts. At the top there's a readout of some relevant stats, the amount of active turfs, how many times the subsystem has fired, etc. You can get the same information from the SSAir MC entry, but it's a bit harder to read. I detail this in the section on performance in environmental atmos. There's a button that turns the subsystem on/off in the top left, it's handy for debugging and seeing how things work step by step. Use it if you need to slow things down. The rest of the panel is where things get more interesting, it's a readout of excited groups, sorted by area name. Most of it ought to be obvious, this is where

An excited group can contain 2 things, sources of diffs, and dead tiles.

Of course, if left unchecked active turfs will spread further and further out, slowly lowering the amount of dead tiles.

Excited group breakdown causes them to recede and wrap around the things causing them

Cleanup causes a major recession due to turfs becoming suddenly no longer having an excited group

Due to how process_cell() works, active turfs will spread strangely when low on diffs

They will also occasionally nap, then immediately wake back up. This is either because of a discrepancy between |